*Part of my reading process is to synthesize and paraphrase major quotes/ideas from the book with my own thoughts to make a book reflection. I enjoy the process of taking the best and most substantive quotes and mashing them together into something more concise. I thought you might get something out of the reflection I created so I've shared it with you below. Unless otherwise noted, all quotes in this reflection come from the book. You can purchase the book HERE.

The successful conclusion of the American Revolution did not guarantee the success of what we now know was the United States of America. Far from it, the victory against the British actually masked an entire mess of problems. The first revolution was about freedom from Britain, but as historian Joseph J. Ellis argued in his book The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, 1783-1789 a second “revolution” was needed to make the thirteen states into a nation. As Ellis puts it, “My argument is that four men made the transition from confederation to nation happen. They are George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison…my contention is that this political quartet diagnosed the systemic dysfunctions under the Articles, manipulated the political process to force a calling of the Constitutional Convention, collaborated to set the agenda in Philadelphia, attempted somewhat successfully to orchestrate the debates in the state ratifying conventions, then drafted the Bill of Rights as an insurance policy to ensure state compliance with the constitutional settlement.”

The “second revolution” that produced the constitution was a monumental achievement led largely by those four individuals. However, every step of the American experiment was just as treacherous and filled with dangers of their own. Every historian understands from even a superficial knowledge of world history (or anyone who has tried to lead anything at any point in their lives) – that having a great constitution/charter/plan/law is one thing and executing that plan is another. The America that inherited the “Quartet’s” second revolution was far from united and a constitution alone would not solve its problems. “In the 1780s – Boston was closer to London in spirit than to its neighbor Charleston geographically. The Revolution had not changed that, and the Revolutionary War’s unifying purpose of Britain as a common enemy was now absent. Regional differences were stark…It only seemed a matter of time before New England’s desire to improve the world would clash with the South’s insistence that it remain just the way it was.” The American experiment was trying to establish a new political unity over thirteen sovereign states with wide gulfs in political and economic culture. The years of war had saddled states with large debts, wrecked economies, ruined trade, and surrounded them with hostile Indian nations as well as opportunistic foreign powers looking to exploit any signs of weakness. If America could not produce a stable, principled, and effective central government (and administrators of that government) that addressed the many problems facing it, it would fall into the dustbin of history. Most of the world felt that a strong monarchy was the only solution to America’s problems. “America was the kind of place that always before and everywhere else had required a crown and council for governance and prosperity, the people knowing their place as subjects, the imperium bound together by the blood of royals, justified by a state-sanctioned church, and sustained by the sword. The rest of the world thought it was only a matter of time before that was America’s fate. The rest of the world could not conceive that Americans did not need a king, could not know that Americans had something better: an improbable Virginia farmer and his unlikely companions. This is their story.”

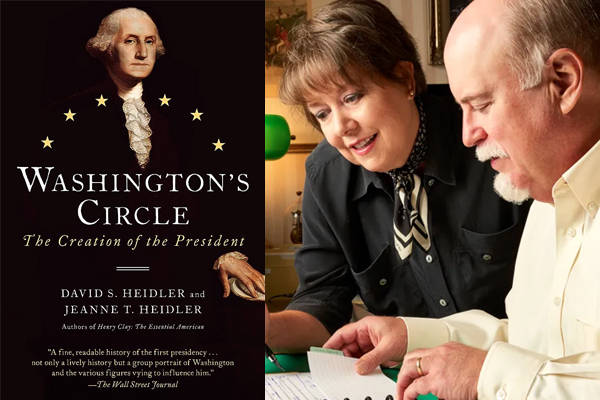

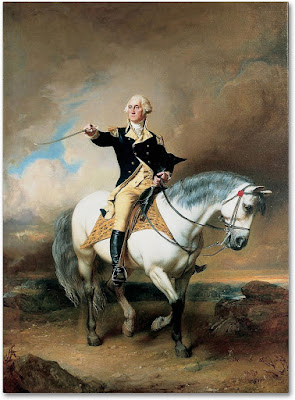

The third large step in cementing the American experiment is the establishment of the government that executed the constitution. David and Jeanne Heidler’s book Washington’s Circle: The Creation of the President steps in wonderfully to explain just how it was accomplished; the people who played the largest roles and their biggest conflicts along the way. It is centered on George Washington, the general who retired to his farm after winning American independence and played a vital role in the second revolution only “to be called back into service to guide the establishment of a republic that could distinguish liberty from license and make government a servant rather than a master.” In addition, their book tells the “story of the people who helped to shape [Washington’s] presidency, people who were indispensable in his final and most demanding job…Washington’s circle helped him summon the finest instincts of a proud and self-reliant people…It’s easy to forget how young they all were when they fought Britain for independence and then set up a government like nothing the world has seen. Because they managed to achieve these feats, they became ‘Founding Fathers,’ and their image for history would be of men always old and often stern. Yet at the beginning of the drama in 1774, Thomas Jefferson was thirty-one, John Jay was twenty-eight, Henry Knox twenty-four, James Madison twenty-three, and Alexander Hamilton only nineteen. George Washington was the relatively ‘old man’ of the group at forty-two, but Washington was one of those people born ‘old.’ The rest were youngsters, and none more so than James Madison. Even the teenager Hamilton looked older.”

In this reflection I’ll begin by summarizing what I think are the most important highlights the Heidler’s share on the key figures of Washington’s circle: James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and Henry Knox. Beyond just tracing individual contributions, the Heidler’s do a good job of identifying key themes/motifs that marked the early administration whether it was the shameful issue of slavery or the dividing powers of partisanship. I will look to share some of my reflections about each of those as well. Finally, I’ll end by remarking upon the interesting traits and anecdotes I learned about the central figure of the book, George Washington. By the time I finished the book, my admiration for him had grown tremendously and I’ll try to explain what the Heidler’s presented that caused it. Let’s turn now to the beginning of Washington’s Presidency, “The country was broke, enemies prowled at its borders…Yet standing at the center of a swirling pool of hope and anxiety was the tall figure with impeccable posture, his head tilted back, his face impassive as his eyes tracked the sparkled arcs of rockets. The odds were long, but that April night in America, anything was possible, even a solvent treasury and peaceful border, even friendly commerce with a world that was spinning its way toward an American dawn. The transparencies told a story, but the rockets rushing upward were more than an ornament. They were an emblem. George Washington and his friends watched them.”

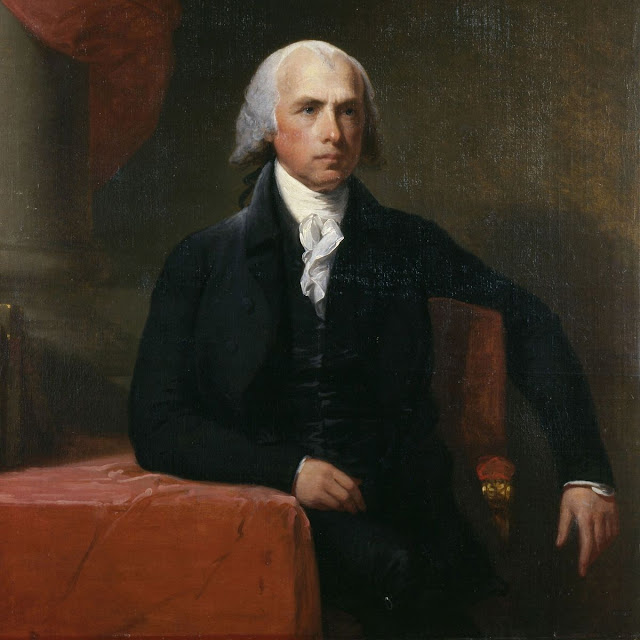

James Madison worked hand in hand with Washington to produce the second revolution and similarly worked hand in hand with Washington to establish the new U.S. government. Madison, however, worked his magic as a member of the newly elected Congress and not as a member of Washington’s historic first Presidential cabinet. The Heidler’s summarize Madison’s role thusly, “James Madison was a trusted counselor who became Washington’s unofficial prime minister, helping to set proper precedents and appropriate relations between the executive and legislative branches. Their partnership was most remarkable, however, for how it slowly, painfully collapsed.”

There are two important insights Madison understood that help to explain his early role in Congress and his close partnership with Washington. Madison understood that the legacy of the American Revolution “rested on the survival of the American union” and the American union would only be successful if the government made real and genuine achievements: “Madison knew that the people’s patience would soon wear thin if the government did not quickly establish sensible procedures and consequently delayed real achievements…Washington knew this as he contemplated the presidency, and Madison’s advice carried the greatest weight with him. In fact, the small man became his closest counselor. It was a natural arrangement as everyone sorted out what the Constitution was meant to do as a form and authority…This sense of urgency made Madison invaluable in hurrying the resolution of important issues…He became President Washington’s ‘prime minister’ in the American House of Commons.”

Madison knew that Congress had to first make good on the promises of amendments to the constitution, but quickly realized that Congress had a way of dissolving into petty and partisan disputes over frivolous topics. Madison navigated the Congress while keeping in constant contact with Washington whom he visited “almost every evening after the House adjourned. They often huddled for hours despite grumbling from those who had thought in Philadelphia that the Senate should be the president’s chief counselor.” In one of my favorite anecdotes of the book, we learn just how influential Madison became in the rhetoric of both the President and Congress: “Washington had worked from Madison’s draft for his inaugural address. Congress then selected Madison to write the House of Representatives’ response to the inaugural address, meaning that Madison was answering an address he had largely written. There was more. Washington asked Madison to write a response to the House’s response and, while he was at it, to write the response to the Senate response as well.”

Madison’s magical way of navigating Congress and articulating Washington’s desires helped to produce the first amendments (becoming known later as the Bill of Rights) to the Constitution that “sought to safeguard the most cherished American principles: freedom of religion, speech, and the press; the right to bear arms and to be tired by a jury; and the right to assemble and petition the government for redress of grievances. Cruel and unusual punishments were forbidden, and private property was guaranteed against arbitrary seizure by the government.” After the submission of the amendments, Madison’s congress created the State Department (July 27, 1789), War Department (August 7), and Treasury Department (September 2). I love Heidler’s comments on this legislative spree, “In creating the executive, Congress found its real strong suit, the one that would exceed all others for all of its history. Congress could debate endlessly, dither over the important, and fixate on the trivial, but it was matchless in its ability to grow government.” Without Madison’s insights and partnership with Washington, it’s conceivable that the early Congress would not have found the urgency to cut through their partisanship and get on with the important work of creating the government (executive departments) and restraining the government (bill of rights). Thank goodness for James Madison!

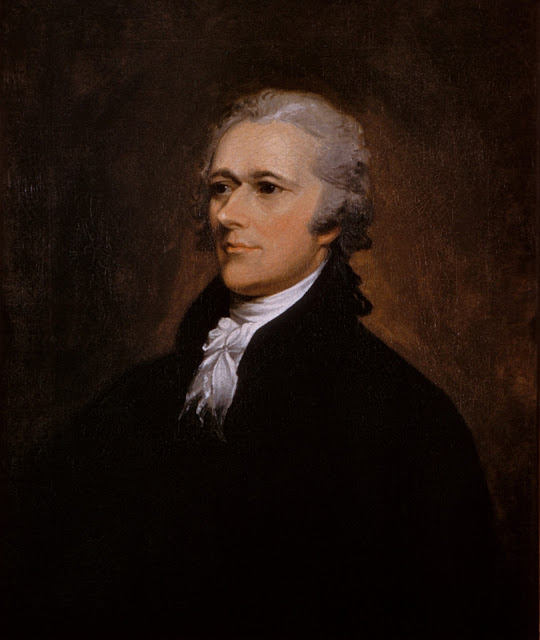

Alexander Hamilton has received a re-appraisal and surge in appreciation in contemporary history thanks in large part to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s fantastic musical Hamilton. With the hindsight we are afforded now, this re-appraisal and surge in appreciation seems well deserving. By the end of Hamilton’s time as Secretary of Treasury “against impossible odds [Hamilton] had put the government on sound financial footing, had groomed a provincial backwater to realize its limitless potential for prosperity, and had persuaded the powerful at home and the British abroad that the United States of America was pure profit waiting to happen.” How did he tackle a problem that stood like the sword of Damocles over the future union of the United States? The Heidler's identify three major financial proposals and three major character traits that helped Hamilton accomplish what he did. Let’s take a look first at the financial proposals.

When Hamilton took up the job as the Secretary of Treasury, America’s financial state was a disaster: “Finances were the government’s biggest problem as trickling revenue allowed an already mountainous public debt to grow while accumulating interest, all in arrears. The amounts were terrifying. The states owed a total of $21 million. Some owed far less than others, which was another complication. The country owed almost $12 million on foreign loans. The central government owed its citizens a whopping $42.5 million. In sum, the total of $75 million could be calculated in modern worth at about $2 trillion in purchasing power but as much as $30 trillion in labor value.” Hamilton would see three major proposals as the path to strengthening the U.S. economy and our image in the world – assumption of all state debts, the establishment of the Bank of the United States, and an enlargement in American manufacturing capability.

These proposals reveal a fundamental economic mindset of Hamilton summarized here by Heidler: “Hamilton was convinced of the general rule that a nation’s standing in the world and with its citizens depended less on its real financial solvency than the perception of its financial solvency. The essential and inescapable reality was clear: Any economic transaction involving credit results in debt, and someone will eventually want the money. The ability to pay that debt carried advantages beyond a tidy ledger with neatly balanced columns of assets and liabilities. It determined the ability to borrow money in the future. Paying off debt was clearly important, but colliding with that goal was the certainty that raising taxes could cripple an economy, making it impossible to function after paying a portion of the bills. The trick was create the confidence that the debt would indeed be paid down, and eventually off, no matter what otherwise happened. The trick was to be achieved through an incredibly complex web of funding over a span of decades rather than years. Central to accepting this protracted schedule was the acceptance of debt as a useful economic tool rather than a burden, the idea that it wasn’t the debt that was the problem, but the kind of creditor who held it. Debt in the right hands – say, America’s wealthiest class – would give the right people a material stake in the country’s survival. They would be compelled to act in the country’s best interests out of their self-interest to be repaid. Hamilton’s policy did not expect good people to do the right thing but made it worthwhile for anybody, good or bad, to do the right thing.”

The complicated financial proposals Hamilton drafted into bills would have probably suffered great defeat if it were not for three important character traits: he was a genius, he worked tirelessly, and he was not a greedy thief. Alexander Hamilton, like James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, was a genius who could grasp complicated topics and articulate his own thoughts with ease. He had an “insatiable quest for self-improvement. He made up for his abbreviated schooling with compulsive reading in broad subjects but always with a specific purpose.” Instead of going through subordinates or finding a congressional partner, it was often easiest to let Hamilton draft his own financial legislation. He would then meet with congressmen to explain his solutions and how they meet the country’s financial needs. Hamilton’s genius and growing treasury department was matched by his work ethic, as Heidler explains, “Hamilton’s reach stretched from his office to the Congress and beyond to the woods of Maine District and the pine barrens of the Georgia frontier…Hamilton was at his desk the Monday after his confirmation and immediately began displaying a superhuman capacity for work. Congress wanted a report on possible ways to address the debt crisis but did not expect it until the second session in early 1790. Even so, that gave Hamilton not much more than a hundred days to gather data and draft some proposals. At the same time, he would have to assemble his department, establish workday routines, install the Customs Service, and staff it with reliable employees. Nobody expected much more than some sketched out ideas in draft form as a starting point for discussion. Nobody yet had any idea that Alexander Hamilton never slept, always worked, and had a mind so acutely honed to the digestion, manipulation, and calculation of numbers that his skills resembled those of an idiot savant – except that Hamilton was all savant and nothing idiotic.”

Along with his genius and work ethic, Hamilton also brought serious problems to the Washington administration, but none of them were theft. Hamilton’s opponents “thought him a big-time crook speculating in bank stock and securities, trading on margins with insider information, and selling influence to jobbers for profit and pleasure. But Hamilton had never personally made a penny on his financial policies. It wasn’t that he was especially scrupulous. He tampered with elections to punish personal enemies, smeared opponents with lies when the truth would serve better and betrayed his wife with a pretty trollop while paying her pimp. But something stayed his hand at Treasury – something his enemies never understood. For Hamilton, theft was vulgar, even when elegantly contrived by aristocratic rogues. Alexander Hamilton might be the bastard child of a Wes Indes slattern and a Scottish peddler, but he wasn’t a thief. The House committee had burned scores of candles scrutinizing the Treasury’s books, ledgers, accounts, reports, letters, and loans for month after month after month, looking for Hamilton’s indiscretions. When it finally filed its findings in the spring of 1795, Republicans closed their eyes and cursed. Their majority immediately tabled the report into oblivion, and for good reason. Nobody could find the slightest impropriety at Treasury on Hamilton’s watch, and the hunt for this hide had become a political embarrassment.”

Following on the footsteps of Madison’s Congressional achievements, Hamilton’s achievements at the Treasury helped bring the United States away from the financial brink and put it on good grounds. Hamilton’s contempoary image as a “selfless patriot who could have made millions in the pursuit of his own interests had he not chosen to pauper himself in the public’s service” seems to be accurate. Washington was wise to place Hamilton at the Treasury and largely unleash him, though it took someone like Washington to tolerate and restrain Hamilton’s often divisive and unfriendly nature. Unfortunately, Hamilton’s major accomplishments along with Washington’s backing made him seem like an “unstoppable political force.” There was bound to be a strong reaction to it.

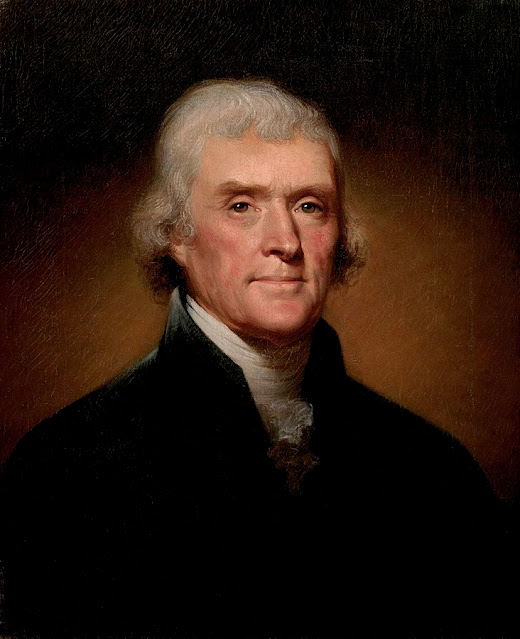

Historian Joseph Ellis calls Thomas Jefferson “The American Sphinx” due to the many seeming contradictions and mysteries wrapped up in his life’s achievements and writings. I have to admit, the more I read about Jefferson, the more I dislike him, and it may or may not be unfair to him. You see, Jefferson is one of those historical characters who are hard to describe on their own (thus the Sphinx moniker) but easier understood as a contrast to others. Heidler describes it like this: “His tenure as secretary of state and his influence on George Washington are difficult to assess outside the partisan battles that produced the First American Party System. But Jefferson functioned outside of those battles, and he accomplished significant things aside from them. He founded the American diplomatic corps and gave it structure and purpose. Along with Hamilton, Jefferson wrote the most influential reports in the history of American government. His work on standardized weights and measures, the fisheries, and on American foreign trade would establish fixed policies or greatly influence them for generations.” For all his genius, you would think a summary of his time at the State Department would find more laurels and thus it’s very hard to define and very easy to criticize. As Heidler said, he is tough to assess outside of his partisan battles and that largely meant his battles with Alexander Hamilton.

No one disputes Jefferson’s genius. In prose that would make anyone jealous, Heidler describes Jefferson as “philosopher and farmer, wordsmith and scientist, a possessor of such an all-encompassing curiosity that nothing escaped his notice, and the wielder of such a marvelous intellect that nothing confounded his understanding, Jefferson had no peers. He had only friends who admired and enemies who hated.” Jefferson’s experience as a statesman and ambassador, particularly with France who was undergoing a revolution of their own, Jefferson was a natural pick to be drawn within Washington’s circle as the Secretary of State.

The two staggering geniuses of Jefferson and Hamilton within Washington’s cabinet were an immediate contrast. They contrasted in their general dress and workstyle: “Alexander Hamilton was always pressed, creased, combed, and crisp, creating the impression that intricate work of amazing detail would naturally flow from an office kept shipshape and Bristol fashion in the images of its boss; Jefferson was always rumpled, preoccupied, mumbling, and delicate, creating the impression of a man constantly searching for a paper he had mislaid. Part of Jefferson’s image was a cultivated affectation, but much of it was the actual expression of his temperament. It disguised a mind of tremendous discipline and immense power.” The two also contrasted immensely in their political philosophies: “Jefferson and Hamilton differed in more basic and essential ideas that represented more than opposing views for the future of America. They personified the choices that have bedeviled Americans from colonial times to ours. When does liberty become a license? When does order become oppression? How does government have enough power to perform its basic functions without incrementally creeping toward intrusiveness and then lurching toward tyranny? It sounds too simple to say Jefferson loved liberty and Hamilton loved order, but that basically distills their sentiments and illuminates their differences, for everything about them stemmed from those core beliefs.”

Rather than an overall drag on the first presidential administration, it seems that Washington was largely able to get these two staggering geniuses to work as complements – at least in his term. Hamilton’s proposals were often met by Jefferson’s critiques and the rest of the cabinet would also chime in. Washington was then able to largely stand between them and decide the best course of action (with the counsel and pen of James Madison of course) for the country. In fact, it’s this dynamic that produced what many consider the first major political compromise for the early government. When Hamilton and Madison were at odds over the assumption of state debts: “Jefferson suggested that Hamilton and Madison work out a solution by meeting privately, possibly over a private dinner at his rented quarters on Maiden Lane the following day, June 20, 1790. Hamilton agreed, and Jefferson seems to have been certain that Madison would as well…According to his account, Jefferson acted as mediator at the dinner with Hamilton, and the results were most promising…Jefferson suggested that establishing the permanent capital on the Potomac could soothe southern members. That observation further suggested that Richard Bland Lee and Alexander White from Potomac districts in Virginia, and Daniel Carroll and George Gale from Maryland districts across the river could be persuaded to abstain when the Senate again sent assumption back to the House as an amendment to the funding bill…By this account, the dinner on June 20, 1790, at Maiden Lane was a historic event and marks the first significant compromise in the history of the federal government. Whether it happened just the way Jefferson recalled or was a less ad hoc series of negotiations does not detract from the obvious fact that some sort of bargain took place that salvaged Hamilton’s plan and placed the permanent capital on the Potomac. It was a first in the American government, but it would be the last for the men who made the arrangement.”

This sense of compromise and working together would unfortunately only last so long: “By early 1792, Washington’s cabinet and informal advisers divided on almost every question that came before them. The pattern of Hamilton and Knox taking one side and Jefferson and Randolph the other was well established by this time.” At this point in American politics, there was no such idea as a “loyal opposition” so those within the government, like Jefferson and increasingly Madison, who began to oppose Hamilton’s proposals consistently and vehemently were presumed to be in a conspiracy to overthrow it – there was no other way to conceive of it at the time. On the other side, Jefferson and Madison were convinced that Hamilton was a monarchist Hamilton’s congressional victories on assumption and later the establishment of the bank would prove too much for Jefferson and Madison. The possibility was there that Hamilton and Jefferson could work together in great complement (as they had largely done before 1792), but eventually their relationship grew too partisan and would produce our first two major American parties as well as put an end to several key relationships: “Thinking the future of the country was at stake made them vicious. By 1792 Madison, Jefferson, and their followers believed their opponents wanted a monarchy or something resembling one…Washington consoled himself that they were men of principle and would not let personal animosity cloud their judgment. He liked to believe that, at least.”

Heidler points to the debate over the bank that seems to have been the key moment of partisan division: “Some historians see the dispute as seminal in the founding of political parties, something that happened despite a universal denunciation of parties as nests of special interests and corrupt practices. Yet the opponents of funding, assumption, and the bank felt more beleaguered than beaten, and by the spring of 1791 they were clustering around the most obvious leader in their ranks, James Madison. The faction was coalescing into a party – some even called it the Madison party – and from the political reality that mirrors Newtonian physics, that action inevitably led to an equal and opposite reaction in the emergence of the Federalist Party. As the development evolved it would complete the estrangement of James Madison from George Washington, neither the first nor the last man to part ways from Washington in sadness and sometimes in anger. The Bank of the United States became a lightning rod as well as a catalyst in this emerging confrontation. When the bank’s stock went on sale during the summer, everything its opponents feared came to pass. Madison had been appalled by the rampant speculation in funding the national debt, but the frenzy to buy bank stock was even more shocking. He and Jefferson watched the old British system of patronage and influence that had corrupted Parliament taking hold in the U.S. Congress. In that summer of 1791 Madison had his question answered about fallen angels: Hamilton was well on his way to creating a moneyed aristocracy that would destroy representative government by setting up an impenetrable and unaccountable system of cronyism and privilege. Members of Congress who scrambled to buy stock in Hamilton’s bank were dancing before a graven idol while tying their material well-being to his policies. They were corrupted, and they sullied the institutions they touched. Madison believed this from his vantage in the legislature. Thomas Jefferson began to see it from his in the administration. It did not help that an odd quid pro quo played out after Washington signed the bank bill. Washington had decided that the federal district should be larger than originally authorized. He asked Congress to pass a supplemental bill to the Residence Act extending the district’s lines to include Alexandria and the area south of the Anacostia River in Maryland. The request seemed routine, but northern members who had objected to the residence deal in the first place apparently held the supplemental bill hostage until Washington approved the bank, which they very much wanted. Sure enough, as soon as Washington signed, the extension of the district passed easily. Jefferson and Madison were helping with the plans for the capital, but they were unsettled by its growing size. The seeming trade of the bank for the district’s enlargement tarred the capital with the bank’s brush.”

The Heidler’s share a wonderful anecdote about a horrendous bout with yellow fever during the summer of 1793 in Philadelphia that perfectly illustrates just how partisanship can poison people against each other: “Relatively few deaths marked its early appearance, and doctors were slow to realize what they faced. By the first week of September, they knew. City leaders did their best to organize medical care and efficient burials. Many people fled, but cities barred fugitives from Philadelphia because of fears of contagion. No one knew what caused yellow fever. In Philadelphia, bad air coming from the harbor’s fetid water was blamed. Mosquitos seemed especially thick during the late summer of 1793, but no one would make the connection for more than a century. All were soon well aware, however, that yellow fever was a horrifying malady that tortured victims before killing them. A low fever, listlessness, and aches signaled its onset. A rising fever soon came on, sometimes to break briefly and rouse hopes of recovery. After a short time, though, the fever would return, raging. A jaundiced complexion gave the disease its name, liver failure being an eventual development, along with internal bleeding, vomiting, and diarrhea. Those who lived alone or were abandoned by frightened relatives died in their own filth. By mid-September, Philadelphia resembled a ghost town. Stores closed, newspapers stopped printing, and government work ceased. Some of Washington’s official family were among the refugees, but Hamilton and Betsey began showing signs of the disease. By September 8, 1793, they were confirmed cases. From his house on the Schuylkill, Jefferson scoffed that Hamilton only had ‘an autumnal fever.’ He sneered that Hamilton had wanted to catch something and chuckled that ‘a man as timed as he is on the water, as timid on horseback, as timid in sickness, would be a phenomenon if the courage of which he has the reputation in military occasions were genuine. It was becoming more and more apparent that public life brought out the worst in the quiet philosopher. Hamilton was treated by Dr. Edward Stevens, who hailed from St. Croix and had been a boyhood friend in the West Indes. Stevens was a product of the University of Edinburgh and subscribed to treating yellow fever with cold baths, a therapy that came to be known as the West Indes treatment. This directly opposed Benjamin Rush’s advocacy of bleeding and blistering, a technique known as the depletion treatment. Bleeding and blistering was Rush’s preferred treatment for everything, and the method often killed rather than cured. Hamilton’s recovery boosted the popularity of the West Indes treatment, and he recommended Stevens and his methods to the college of physicians. Yellow fever, like everything else, showed the country’s preoccupation with politics. Steven’s West Indes treatment was cited as the Federalist cure and Rush’s depletion method as the Republican one.” With our recent experience of the Covid pandemic, it’s not hard to see the historical parallels here. Partisanship has a way of poisoning our discourse, turning us into unfeeling and unthinking tribal participants. It’s one heck of a problem.

Ironically, this growing partisanship is both a reason why George Washington wanted to retire after just one term and a reason why everyone needed to keep serving. Washington made it clear to Hamilton, Jefferson, Knox, Randolph, and Madison that he longed to return to his farm as his health was growing worse, the partisanship of the country was getting to him, and someone better qualified to the position was surely available. Washington told Madison that he “'from the beginning found himself deficient in many of the essential qualifications for the job.’ It was somebody else’s time now.” The counsel he received told him that Washington’s retirement would be bad for the country: “Jefferson told Washington that if he retired, political divisions would become so venomous that the country would not likely survive. Jefferson described a government corrupted by Hamilton’s financial policies, its citizens developing ‘habits of vice and idleness instead of industry and morality,’ and a Congress either blind to or collaborating in the perversion of the American experiment…he knew that without Washington all would be lost…Washington then wrote heartfelt appeals to both men, urging them to put aside their differences for the good of the country. The United States had many enemies. Infighting encouraged those enemies while riling the people. Washington hoped ‘that liberal allowances will be made for the political opinions of one another,’ for without the effort he could ‘not see how the Reins of Government are to be managed, or how the Union of the States can be much longer preserved.’…Washington still hoped to bring the two together." They would never reconcile.

Unfortunately, while both Jefferson and Hamilton would sign on to the second term, they would resign in 1793 and 1795 respectively. Washington’s second cabinet did not see the major successes of his first: “Nothing more vividly illuminates the diminished talent of Washington’s second cabinet than this fact – that he had to choose people because they were available…They were not untalented for ordinary times, but they were plopped into place during extraordinary events. They were also much less sophisticated than Jefferson and Hamilton. Unlike those two, for example, Wolcott could not read French and Pickering could make out only a little, which was worse, as it turned out.”

Jefferson left for Monticello in 1793 and his removal from the inside of Washington's circle unfortunately only turned him more partisan and venomous. Sadly, Jefferson’s departure served to remove the counterbalance he naturally brought to the influence of Hamilton and the Federalists on Washington. Both great men, Jefferson and Washington, “lost the balance that had existed, if uneasily, while they worked together for the same ends – a strong, stable, republican government accountable to a free and happy people. Americans wanted the country Thomas Jefferson envisioned; they got the government Alexander Hamilton planned.”

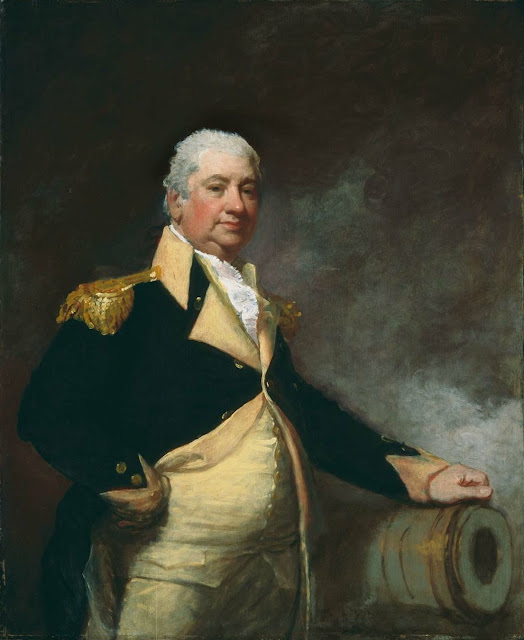

When your first cabinet includes Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, it’s easy to understand why Henry Knox doesn’t always get the attention he deserves. However, Washington wouldn’t have thought of Knox as a lesser among those two great men: “Of all the men in his official family, he knew Henry Knox best. Washington relied on the stellar lights of his administration for expert advice, but he planned to rely on good old reliable Henry Knox for something else. Washington could confide in Knox about anything with greater ease than with any other man because of what they had done together in the most titanic event of George Washington’s life, which was the American Revolution.” The problems facing the Secretary of War were immense: “The land from the Great Lakes to Spanish Louisiana and Florida was in turmoil as land speculators encouraged settlers to move deeper into the wilderness. When Indians violently resisted these encroachments, settlers appealed to state and national governments for protection. In addition to the complication posed by the British occupation of forts in the Northwest, British fur traders wanted to keep their trapping grounds free of settlers. This made the northwestern and the Kentucky frontiers especially volatile, and the bulk of the nation’s meager military forces were stationed there. When Washington took office, however, the South became a pressing problem. Spanish trade provided the Indians with guns and ammunition, making the two powerful Indian confederations of Creeks and Cherokees armed as well as angry.” In summary, “Knox had to run a military department that lacked a military and cope with war scares that loomed and receded in a dangerous world.”

One of the great achievements for Knox was the Treaty of New York signed with the Muscogee tribes helping to assuage some of the country’s frontier issues: “The Treaty of New York was an impressive agreement, despite its coarser appeals to vanity with foolish army commissions and outright bribes, for it was an attempt to set a new tone in relations between the extant people of a place who found themselves unwittingly part of a new political order…It was Henry Knox’s most impressive achievement.” Knox ultimately wanted to deal with the Indian problem through a “civilization plan” that sought to assimilate Native Americans to the English language and American culture. Washington would eventually agree with this direction and though ultimately naïve, seems to have been born of good motives.

By the end of his tenure, Knox was a crucial friend and counselor to Washington, he managed to keep the United States out of numerous possible wars. “He grew to despise the Congress for its parsimony and to loathe the state governments for their stubborn refusal to make their militias a viable, unified fighting force. He became a thorough nationalist, a strong supporter of the Constitution” and possibly one of the most unrecognized factors in Washington’s circle in producing a stable government.

There’s likely no more glaring contradiction to the hallowed principles of the American Declaration of Independence, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,” than the institution of American slavery. The first revolution was about freedom from Britain, the second revolution was about drafting a constitution to hold the country together, and Washington’s presidency was about creating a government that would make good on the promises and legacy of the first two revolutions. So how did Washington and his circle see and react to slavery?

In general: Slavery was seen as a fact of life in the American states. The Heidler’s identify Martha Washington’s feelings on slavery as typical of most white British North Americans: “Slavery was part of the way things were, part of the system of rank and caste that, for all she knew, affected the lives of all people everywhere. In her view of the world, the obligation of whites within the system of slavery was to make it as tolerable as possible with kindness and forbearance…This was the case throughout her life, beginning at Chestnut Grove, continuing at the White House, and then over the years at Mount Vernon. She believed that the people living in slavery also accepted it as the natural way of things.” Slavery was increasingly something people did not want to talk about: “Southerners did not want to talk about it because it embarrassed or angered them. They felt the stain of hypocrisy with their high talk of liberty, and they feared the prospect of abolition because it was economically disastrous and socially terrifying. The ‘reasonable’ position held that the debates raised unnecessarily provocative issues best left alone, which made the problem insoluble.”

James Madison: “Yet Madison made no arrangements in his will to free a single slave. This brilliant child of the Enlightenment with an all-encompassing mind and boundless vision could never see beyond the coffles, shackles, and skin.”

Thomas Jefferson: “Unlike Madison, Thomas Jefferson seems to have thought about slavery a lot. Jefferson never reconciled his devotion to liberty with his ownership of slaves, which left him open to charges of hypocrisy for his entire public career. Also like Madison, his belief in the inherent intellectual and physical inferiority of people of African descent kept him from publicly denouncing slavery…Many scholars doubt that Jefferson, despite his soaring words and admirable aims, ever seriously opposed slavery other than as a mere philosophical exercise. The spring was never wound tighter in Thomas Jefferson than on this issue, a jumble of conflicts and hypocrisies that Madison had all but resolved not to think about, while Jefferson apparently thought about it more or less all the time. ‘I tremble for my country,’ he said as he surveyed slavery, ‘when I reflect that God is just; that his justice cannot sleep forever.’”George Washington: “George Washington had owned slaves for as long as he could remember, beginning with his inheritance of ten people from his father. As with Martha, for much of his adult life the immorality of slavery did not trouble him because it did not occur to him. His was a world built by, powered by, and framed by slavery – and not just in Virginia, nor just in the southern colonies. This was the world as these people found it…Slaves were meant to work, and Washington believed that the very nature of slavery discouraged them from doing so with any enthusiasm. They could not improve their good names, and they could not add luster to their reputations. He would not work slaves who were ill, but he also would not be taken advantage of. Doctors were consulted, if necessary, not only to treat the ill but also to determine if sicknesses were feigned. By the year of Washington’s death, 1799, more than three hundred slaves lived at Mount Vernon, far more than were needed to run the place efficiently.”

After the revolution Washington began to loathe slavery, seeing in it the immorality and hypocrisy, and considered emancipation. However, he knew it remained a problem with many difficulties practically, politically, and economically. “During the years he seriously pondered emancipation, he had to face the reality that he did not own more than half of the slaves who worked at Mount Vernon. They were legally designated as ‘dower slaves’ and had come to him through his marriage to Martha…Edward Savage’s painting ‘The Washington Family’ included a black ‘servant’ standing behind Martha in shadows, and this was likely William Lee. Savage dressed him in something other than livery with a vibrantly colored vest, an arresting contrast to the dark background where he stands. His face if not his clothes is almost swallowed by the shadows. Savage, like other artists who included Lee in their portraits of Washington, took pains to make clear he was wholly African, which he was not. In some reproductions of the Savage painting over the years, Lee becomes nothing at all. He simply vanishes. As some have suggested, placing him in the shadows was perhaps an apt metaphor for slavery in the early republic. Making him go away altogether could seem an appropriate allegory for what happened to him at Mount Vernon after he shattered his legs. In that, William Lee’s life seems to stand as evidence for Washington’s coldness as well as his habit of avoiding the inconvenient hypocrisies of slavery. To his credit, in the end he addressed this. He drew up a will that gave his slaves their freedom after Martha’s death. (he could do nothing for the dower slaves.) Washington made William Lee the only slave to receive freedom immediately without waiting for Martha’s death. Lee could at his choice leave Mount Vernon or remain. In either case, he was to receive $30 ever year, a sum with a modern value of about $600. After all the years of pondering, he finally reasoned out how to deal with slavery: For the part of it in his power, he would end it. William Lee remained at the estate and would die there eleven years after Washington’s death. Possible leaving everything he had ever known was too overwhelming to undertake, especially for a man with his legs. If so, he was a casualty of a system that crushed men’s spirit as much as their dignity, making too many of them people who did not know how to be free. He often drank more whiskey than was good for him and had a comfortable annuity to keep it flowing, but in the end he had more than that. If was at least some measure of proof that his companion of old had not cast him off. It wasn’t the money or the roof, George Washington bestowed on this good man a unique mark of respect. In his will, the first-person Washington mentioned by name was Martha. The second was William Lee.”

Finally, we turn to the titular man himself, George Washington. It’s obvious that Washington has had an outsized impact on our country and has a place of reverence among American historians, but the more details and anecdotes I learned about him, the more I wondered if we haven’t honored this man enough. The American experiment had every chance to fail, every reason to bet against, and if history is any indication, should have broken into petty disputes and regional sovereignties rather than remain a union. As we have learned already, Washington was blessed with incredible talents in his first cabinet and a right hand man with a common cause in the Congress. Still, such advantages are often squandered by kings and generals. What was it about George Washington that allowed him to cultivate those blessings? To paraphrase the most enduring phrase about Washington, what was so special about George Washington that made him first in war, first in peace, and first in the heats of his countrymen? I’d like to point out a few things Heidler shines light on.

First, Heidler points out Washington’s commanding size, which is something that we often forget about the man: “He was an enormous man for his time, standing six feet three inches with enviable posture and a muscular physique. His arms and legs were long, his hands and feet large. He had broad shoulders, but broad hips as well, making him pear-shaped with a relatively small chest and thin torso. His neck was strong, and his face was pleasantly proportioned with blue eyes set somewhat far apart. He had a heavy brow, a strong chin, and a prominent nose whose wide bridge gave him the appearance of an inscrutable lion…It was the rare instance of a man being larger than life both as an image and a person.”

Second, Washington’s temperament seemed finely tuned, along with his unusual size, for being a figure who commands authority without having to become despotic: “The contrasting elements of his temperament marked a special quality in George Washington, one that made his seemingly incongruous parts into a harmonious whole. He was obsessed with exerting control but careful to avoid abusing the power that came with it. He wanted the farms at Mount Vernon to run with clockwork efficiency but allowed the deer to run rampant. He wanted the new government to provide stability and security but was committed to limiting its authority and constraining its reach. He was reluctant to serve but was willing to sacrifice. It all made him particularly suited for accomplishing something even more incredible than winning the Revolutionary War and tiring to his farms…His sense of dignity was highly developed and his manner cordial but detached. Except in extremely rare instances, Washington had acolytes rather than friends, and adversaries usually became enemies.” There’s a real sense that during the Constitutional Convention that the Presidency was written and crafted with Washington and his temperament in mind.

Third, Washington was not eager to take up the reigns of power. He was a rare breed in power politics - a reluctant leader. Washington’s years “following the end of the Revolutionary War had made him happy. He grew things on the ground above the majestic river he loved, living in the house he loved with the woman he loved…” Washington was now older, tired, and retired with the belief that his legacy was intact. Taking up the task of the Presidency was “the play not only untried but unwritten, and the supporting cast was uncertain.” Washington had every excuse to demur and stay on his farm in his old age. After reluctantly agreeing to serve and completing by all accounts a very successful first term, Washington wanted to again retire to his farm and let others take the reigns of power. Those in the know however, knew that Washington’s temperament and character were needed at such a moment in history to hold back the partisanship, corruption, and foolishness that has undone most every new government in history – let alone an experimental republic! In fact, the Heidler’s comment that “Nothing stood in the way of George Washington’s remaining president for the rest of his life, and most people had expected him to.” The only thing that stood in the way was Washington’s character and desire to rest. This genuine reluctance mixed with a willingness to serve at great personal sacrifice is so rare to find in the circles of power Washington found himself. It’s no wonder those who surrounded him worried greatly for the nation once Washington stepped down at the end of his second term. How many like him were around?

Fourth, Washington brought both a serious “above the politics” dignity and a hard work ethic to the office. The Presidency, depending on the man in office, could have easily turned into an elected monarch – with the President tasting all the fine sweets of the office and largely using the position to his pleasure. Washington spent much time in thinking through and crafting with his cabinet exactly what the president of a republic should do with his day and how he should interact with the rest of the government and the people. In handling cabinet discussions or meeting with dignitaries Washington’s impairments and minor faults ironically worked to give him an air of dignity: “the deliberation that could exasperate quicker men was just right for the task he shouldered. He was a bit deaf and growing deafer, but that made him seem impervious to chattering arguments. He paused and hesitated when he spoke, but that made him seem thoughtfully averse to hair-triggered opinions. Saddled with ordinary flaws, Washington forged them into armor that protected him, burnished his reputation, and increased people’s admiration.”

The Heidler’s share a fascinating anecdote from Washington’s presidency that demonstrates the kind of “I must remain calm and stable despite my suffering” for the better of the country mindset that Washington took to the office: “Horseback riding was Washington’s favorite exercise, and after arriving in New York he worked off nervous energy by overdoing it. It almost killed him. In mid-June, a small irritation on his left buttock changed from a minor saddle sore to a painful boil. Mindful of presidential dignity, public reports described the wound’s location as Washington’s upper thigh, but nothing in the days that followed could disguise the fact that it was turning into a serious infection. As it grew outward and inward, a ‘very large tumor’ hardened beneath the skin and a ‘disorder commenced in a fever which…greatly reduced him.’ The illness was doing much more than greatly reducing him. By the time the doctors hurred ti Cherry Street, Washington was lucky to be alive. The physicians instantly recognized the malady. Cutaneous anthrax is usually transmitted by an open wound’s contact with an infected animal, which is likely what had turned Washington’s carbuncle into the telltale sore of flaming red skin with a black circle in the center, the site of the infection. The doctors measured the mass as the size of two fists and judged his fever high enough to be ‘threatening.’ Washington recognized a euphemism better than most and wanted the hard truth instead, even if it was the worst news possible. ‘Whether tonight, or twenty years hence, it makes no difference,’ he said. ‘I know that I am in the hands of a good providence.’ The doctors were not ready to hand him off just yet, but the need for immediate surgery to save his life invited equally dangerous infections. They had no choice. Washington consented to the operation. Two physicians, a father and son, came to the bedroom at Cherry Street on June 17, 1789, to conduct a procedure more resembling a butcher’s job than a doctor’s. After a brief preparation, the son’s scalpel commenced cutting away the infected mass, but there seemed no end to it, and the initial cut turned into a wholesale excavation. Washington had no anesthesia but neither flinched nor made a sound. The father knew that leaving in place any trace of infection would make the operation pointless, so he finally blurted out as his son paused, ‘Cut away – deeper, deeper still!’ The son continued slicing. ‘Don’t be afraid,’ the father exclaimed, not to Washington, but to his son; he glanced at the president, certainly in amazement, and said, ‘You see how well he bears it!’ Washington bore it well enough to let them finish the grisly task and close the wound. A silent crowd had assembled on Cherry Street…By late June, Washington’s fever had broken and his appetite returned. The doctors knew he would live, but he was badly mangled and could not sit normally for weeks.”

Along with this noble dignity, Washington brought a disciplined work ethic to the office. You can see in the following explanation just how purposeful Washington was in spending time working for the country, working with others, and yet retaining time for his family: “As he did in Virginia, Washington kept to the same schedule each day. He rose early, usually before the servants and ambled through the house. He inspected the stables, pulled up horses’ hooves to see about shoes, rubbed their noses, maybe pulled a carrot from his pocket for a treat, and watched with emotionless blue eyes as it was crunched down. Back inside he read newspapers and answered mail. He had been up for hours by the time he had breakfast with the family at seven o’clock. Then he worked with the secretaries and met appointments, one after another and seemingly without end. His exercise was either on horseback or a brisk walk in the neighborhood before the midafternoon dinner with the families, the official one of secretaries (‘the gentlemen of the household’) and the other of his kin. Afterward, he returned to work until eight P.M., had a light supper, and gathered again with family. When conversation lagged, someone read aloud, often Toby Lear. The household was in bed by ten o’clock at the latest. The next morning was the same, as was the next. The levees, dinners, and impressive entourage were the public face of the president’s existence, but George Washington’s evenings were altogether different. Nelly played the harpsichord. Toby read aloud. Martha sewed. That was George Washington’s glamorous and regal life as the president of the United States. The public knew nothing of this, which was too bad.”

Throughout his two terms, “George Washington, on the other hand, was the face of rectitude, calm, and steady honesty, the father of his country. Every American was his friend, and they were terrified over losing him.” I would suggest one other major trait that turned Washington into the figure we so greatly admire – his Christian faith: “Washington’s first deed after the inauguration ceremony was to go to church.” But weren’t all the founding fathers Deists? Several were, but it’s hard to lump Washington into that category. A closer inspection by the Heidlers reveal a much more active and transformational Christian faith than that of Deism: “This was not Deism, a creation of the Enlightenment that appealed to the rationalism of intellectuals uncomfortable with the supernatural aspects of religion. The God of Deism was detached, a master mechanic who had created a perfect machine that once thumped into motion ran perpetually without the need for superintendence and certainly without random instances of divine intervention. Deism is often toured as the faith of the American founders, which makes the mistake of lumping all Deists together by ignoring that Deism was no more monolithic than denominational Christianity. Jefferson and Franklin are always cited as the most obvious Deists, and Washington is frequently added to the list as a passive participant – a reluctant Anglican at best, a secular realist at heart. Yet, his inaugural address contained the same sentiments he expressed throughout his life. His reference to the ‘sacred fire of liberty’ echoed his self-admonition meticulously copied from a seventeenth-century text, Rules of Civility & Decent Behaviour in Company and Conversation, when Washington was only a teenager: ‘Keep alive in Your Breast that Little Spark of Celestial fire Called Conscience.’…Even though Washington never explicitly explained his own beliefs in a concise manifesto, he obviously believed in God as a participant, ‘an agency,’ in the lives of men and women and nations. His recurring references to a supreme being coincided with his habit of often quoting the Bible in his letters, demonstrating a clear and thorough knowledge of the Old and New Testaments. Possibly Washington set aside time in the early morning for private prayer. He plainly directed that grace precede meals at his table. He attended church regularly, served on his Episcopal vestry, and supported the church financially. He made no secret of his belief that active church membership was an important seam in a community’s fabric that tied society together. Moreover, to take Washington at his word in scores of writings that mirror his inaugural address, he believed that religion in general and Christianity in particular were essential to the success of republican government. Religion encouraged civic virtue and responsibility. During the Revolution, he ordered soldiers to attend religious services. While president, he rarely missed Sunday services, and his only activity on the Sabbath was the appropriately restful one of writing his lengthy letters to Mount Vernon’s managers”

In the long scope of history, America was truly blessed to have such a grouping of men as Washington and his circle in such a tremendous time of need. The country had a million ways it could crash and burn and such a narrow path to success, but Washington left his final term as president with “the country more prosperous, more stable, and just as free as he had found it. It would be strong enough to handle the crises to come. Americans credited Washington with these achievements, because few doubted his ‘purity of motive,’ and they were confident that because of George Washington a bright future was coming to life for them ‘in the womb of time.’” Given what you’ve read so far, it’s probably not that surprising that after winning American independence, crafting its second revolution, and establishing it on stable ground as its first president, Washington headed back to his farm to quietly live out the rest of his life: “In Washington’s final retirement, people came in large numbers every day of the week, every day of the year. The only time the Washingtons were not personally extending the hospitality of their home was when they were visiting nearby family or friends. Even so, strangers with letters of introduction or strangers with merely open hands and empty stomachs continued to appear and were never turned away. When in residence, Washington followed his routine of rising early, writing letters, eating a quick breakfast, and riding his farms. He returned an hour before dinner, still held at three o’clock, sharp.” What a remarkable man.

In this reflection I’ll begin by summarizing what I think are the most important highlights the Heidler’s share on the key figures of Washington’s circle: James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and Henry Knox. Beyond just tracing individual contributions, the Heidler’s do a good job of identifying key themes/motifs that marked the early administration whether it was the shameful issue of slavery or the dividing powers of partisanship. I will look to share some of my reflections about each of those as well. Finally, I’ll end by remarking upon the interesting traits and anecdotes I learned about the central figure of the book, George Washington. By the time I finished the book, my admiration for him had grown tremendously and I’ll try to explain what the Heidler’s presented that caused it. Let’s turn now to the beginning of Washington’s Presidency, “The country was broke, enemies prowled at its borders…Yet standing at the center of a swirling pool of hope and anxiety was the tall figure with impeccable posture, his head tilted back, his face impassive as his eyes tracked the sparkled arcs of rockets. The odds were long, but that April night in America, anything was possible, even a solvent treasury and peaceful border, even friendly commerce with a world that was spinning its way toward an American dawn. The transparencies told a story, but the rockets rushing upward were more than an ornament. They were an emblem. George Washington and his friends watched them.”

JAMES MADISON – “The Unofficial Prime Minister”

James Madison worked hand in hand with Washington to produce the second revolution and similarly worked hand in hand with Washington to establish the new U.S. government. Madison, however, worked his magic as a member of the newly elected Congress and not as a member of Washington’s historic first Presidential cabinet. The Heidler’s summarize Madison’s role thusly, “James Madison was a trusted counselor who became Washington’s unofficial prime minister, helping to set proper precedents and appropriate relations between the executive and legislative branches. Their partnership was most remarkable, however, for how it slowly, painfully collapsed.”

There are two important insights Madison understood that help to explain his early role in Congress and his close partnership with Washington. Madison understood that the legacy of the American Revolution “rested on the survival of the American union” and the American union would only be successful if the government made real and genuine achievements: “Madison knew that the people’s patience would soon wear thin if the government did not quickly establish sensible procedures and consequently delayed real achievements…Washington knew this as he contemplated the presidency, and Madison’s advice carried the greatest weight with him. In fact, the small man became his closest counselor. It was a natural arrangement as everyone sorted out what the Constitution was meant to do as a form and authority…This sense of urgency made Madison invaluable in hurrying the resolution of important issues…He became President Washington’s ‘prime minister’ in the American House of Commons.”

Madison knew that Congress had to first make good on the promises of amendments to the constitution, but quickly realized that Congress had a way of dissolving into petty and partisan disputes over frivolous topics. Madison navigated the Congress while keeping in constant contact with Washington whom he visited “almost every evening after the House adjourned. They often huddled for hours despite grumbling from those who had thought in Philadelphia that the Senate should be the president’s chief counselor.” In one of my favorite anecdotes of the book, we learn just how influential Madison became in the rhetoric of both the President and Congress: “Washington had worked from Madison’s draft for his inaugural address. Congress then selected Madison to write the House of Representatives’ response to the inaugural address, meaning that Madison was answering an address he had largely written. There was more. Washington asked Madison to write a response to the House’s response and, while he was at it, to write the response to the Senate response as well.”

Madison’s magical way of navigating Congress and articulating Washington’s desires helped to produce the first amendments (becoming known later as the Bill of Rights) to the Constitution that “sought to safeguard the most cherished American principles: freedom of religion, speech, and the press; the right to bear arms and to be tired by a jury; and the right to assemble and petition the government for redress of grievances. Cruel and unusual punishments were forbidden, and private property was guaranteed against arbitrary seizure by the government.” After the submission of the amendments, Madison’s congress created the State Department (July 27, 1789), War Department (August 7), and Treasury Department (September 2). I love Heidler’s comments on this legislative spree, “In creating the executive, Congress found its real strong suit, the one that would exceed all others for all of its history. Congress could debate endlessly, dither over the important, and fixate on the trivial, but it was matchless in its ability to grow government.” Without Madison’s insights and partnership with Washington, it’s conceivable that the early Congress would not have found the urgency to cut through their partisanship and get on with the important work of creating the government (executive departments) and restraining the government (bill of rights). Thank goodness for James Madison!

ALEXANDER HAMILTON – The Secretary of the Treasury

When Hamilton took up the job as the Secretary of Treasury, America’s financial state was a disaster: “Finances were the government’s biggest problem as trickling revenue allowed an already mountainous public debt to grow while accumulating interest, all in arrears. The amounts were terrifying. The states owed a total of $21 million. Some owed far less than others, which was another complication. The country owed almost $12 million on foreign loans. The central government owed its citizens a whopping $42.5 million. In sum, the total of $75 million could be calculated in modern worth at about $2 trillion in purchasing power but as much as $30 trillion in labor value.” Hamilton would see three major proposals as the path to strengthening the U.S. economy and our image in the world – assumption of all state debts, the establishment of the Bank of the United States, and an enlargement in American manufacturing capability.

These proposals reveal a fundamental economic mindset of Hamilton summarized here by Heidler: “Hamilton was convinced of the general rule that a nation’s standing in the world and with its citizens depended less on its real financial solvency than the perception of its financial solvency. The essential and inescapable reality was clear: Any economic transaction involving credit results in debt, and someone will eventually want the money. The ability to pay that debt carried advantages beyond a tidy ledger with neatly balanced columns of assets and liabilities. It determined the ability to borrow money in the future. Paying off debt was clearly important, but colliding with that goal was the certainty that raising taxes could cripple an economy, making it impossible to function after paying a portion of the bills. The trick was create the confidence that the debt would indeed be paid down, and eventually off, no matter what otherwise happened. The trick was to be achieved through an incredibly complex web of funding over a span of decades rather than years. Central to accepting this protracted schedule was the acceptance of debt as a useful economic tool rather than a burden, the idea that it wasn’t the debt that was the problem, but the kind of creditor who held it. Debt in the right hands – say, America’s wealthiest class – would give the right people a material stake in the country’s survival. They would be compelled to act in the country’s best interests out of their self-interest to be repaid. Hamilton’s policy did not expect good people to do the right thing but made it worthwhile for anybody, good or bad, to do the right thing.”

The complicated financial proposals Hamilton drafted into bills would have probably suffered great defeat if it were not for three important character traits: he was a genius, he worked tirelessly, and he was not a greedy thief. Alexander Hamilton, like James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, was a genius who could grasp complicated topics and articulate his own thoughts with ease. He had an “insatiable quest for self-improvement. He made up for his abbreviated schooling with compulsive reading in broad subjects but always with a specific purpose.” Instead of going through subordinates or finding a congressional partner, it was often easiest to let Hamilton draft his own financial legislation. He would then meet with congressmen to explain his solutions and how they meet the country’s financial needs. Hamilton’s genius and growing treasury department was matched by his work ethic, as Heidler explains, “Hamilton’s reach stretched from his office to the Congress and beyond to the woods of Maine District and the pine barrens of the Georgia frontier…Hamilton was at his desk the Monday after his confirmation and immediately began displaying a superhuman capacity for work. Congress wanted a report on possible ways to address the debt crisis but did not expect it until the second session in early 1790. Even so, that gave Hamilton not much more than a hundred days to gather data and draft some proposals. At the same time, he would have to assemble his department, establish workday routines, install the Customs Service, and staff it with reliable employees. Nobody expected much more than some sketched out ideas in draft form as a starting point for discussion. Nobody yet had any idea that Alexander Hamilton never slept, always worked, and had a mind so acutely honed to the digestion, manipulation, and calculation of numbers that his skills resembled those of an idiot savant – except that Hamilton was all savant and nothing idiotic.”

Along with his genius and work ethic, Hamilton also brought serious problems to the Washington administration, but none of them were theft. Hamilton’s opponents “thought him a big-time crook speculating in bank stock and securities, trading on margins with insider information, and selling influence to jobbers for profit and pleasure. But Hamilton had never personally made a penny on his financial policies. It wasn’t that he was especially scrupulous. He tampered with elections to punish personal enemies, smeared opponents with lies when the truth would serve better and betrayed his wife with a pretty trollop while paying her pimp. But something stayed his hand at Treasury – something his enemies never understood. For Hamilton, theft was vulgar, even when elegantly contrived by aristocratic rogues. Alexander Hamilton might be the bastard child of a Wes Indes slattern and a Scottish peddler, but he wasn’t a thief. The House committee had burned scores of candles scrutinizing the Treasury’s books, ledgers, accounts, reports, letters, and loans for month after month after month, looking for Hamilton’s indiscretions. When it finally filed its findings in the spring of 1795, Republicans closed their eyes and cursed. Their majority immediately tabled the report into oblivion, and for good reason. Nobody could find the slightest impropriety at Treasury on Hamilton’s watch, and the hunt for this hide had become a political embarrassment.”

Following on the footsteps of Madison’s Congressional achievements, Hamilton’s achievements at the Treasury helped bring the United States away from the financial brink and put it on good grounds. Hamilton’s contempoary image as a “selfless patriot who could have made millions in the pursuit of his own interests had he not chosen to pauper himself in the public’s service” seems to be accurate. Washington was wise to place Hamilton at the Treasury and largely unleash him, though it took someone like Washington to tolerate and restrain Hamilton’s often divisive and unfriendly nature. Unfortunately, Hamilton’s major accomplishments along with Washington’s backing made him seem like an “unstoppable political force.” There was bound to be a strong reaction to it.

THOMAS JEFFERSON – The Secretary of State

Historian Joseph Ellis calls Thomas Jefferson “The American Sphinx” due to the many seeming contradictions and mysteries wrapped up in his life’s achievements and writings. I have to admit, the more I read about Jefferson, the more I dislike him, and it may or may not be unfair to him. You see, Jefferson is one of those historical characters who are hard to describe on their own (thus the Sphinx moniker) but easier understood as a contrast to others. Heidler describes it like this: “His tenure as secretary of state and his influence on George Washington are difficult to assess outside the partisan battles that produced the First American Party System. But Jefferson functioned outside of those battles, and he accomplished significant things aside from them. He founded the American diplomatic corps and gave it structure and purpose. Along with Hamilton, Jefferson wrote the most influential reports in the history of American government. His work on standardized weights and measures, the fisheries, and on American foreign trade would establish fixed policies or greatly influence them for generations.” For all his genius, you would think a summary of his time at the State Department would find more laurels and thus it’s very hard to define and very easy to criticize. As Heidler said, he is tough to assess outside of his partisan battles and that largely meant his battles with Alexander Hamilton.

No one disputes Jefferson’s genius. In prose that would make anyone jealous, Heidler describes Jefferson as “philosopher and farmer, wordsmith and scientist, a possessor of such an all-encompassing curiosity that nothing escaped his notice, and the wielder of such a marvelous intellect that nothing confounded his understanding, Jefferson had no peers. He had only friends who admired and enemies who hated.” Jefferson’s experience as a statesman and ambassador, particularly with France who was undergoing a revolution of their own, Jefferson was a natural pick to be drawn within Washington’s circle as the Secretary of State.

The two staggering geniuses of Jefferson and Hamilton within Washington’s cabinet were an immediate contrast. They contrasted in their general dress and workstyle: “Alexander Hamilton was always pressed, creased, combed, and crisp, creating the impression that intricate work of amazing detail would naturally flow from an office kept shipshape and Bristol fashion in the images of its boss; Jefferson was always rumpled, preoccupied, mumbling, and delicate, creating the impression of a man constantly searching for a paper he had mislaid. Part of Jefferson’s image was a cultivated affectation, but much of it was the actual expression of his temperament. It disguised a mind of tremendous discipline and immense power.” The two also contrasted immensely in their political philosophies: “Jefferson and Hamilton differed in more basic and essential ideas that represented more than opposing views for the future of America. They personified the choices that have bedeviled Americans from colonial times to ours. When does liberty become a license? When does order become oppression? How does government have enough power to perform its basic functions without incrementally creeping toward intrusiveness and then lurching toward tyranny? It sounds too simple to say Jefferson loved liberty and Hamilton loved order, but that basically distills their sentiments and illuminates their differences, for everything about them stemmed from those core beliefs.”

Rather than an overall drag on the first presidential administration, it seems that Washington was largely able to get these two staggering geniuses to work as complements – at least in his term. Hamilton’s proposals were often met by Jefferson’s critiques and the rest of the cabinet would also chime in. Washington was then able to largely stand between them and decide the best course of action (with the counsel and pen of James Madison of course) for the country. In fact, it’s this dynamic that produced what many consider the first major political compromise for the early government. When Hamilton and Madison were at odds over the assumption of state debts: “Jefferson suggested that Hamilton and Madison work out a solution by meeting privately, possibly over a private dinner at his rented quarters on Maiden Lane the following day, June 20, 1790. Hamilton agreed, and Jefferson seems to have been certain that Madison would as well…According to his account, Jefferson acted as mediator at the dinner with Hamilton, and the results were most promising…Jefferson suggested that establishing the permanent capital on the Potomac could soothe southern members. That observation further suggested that Richard Bland Lee and Alexander White from Potomac districts in Virginia, and Daniel Carroll and George Gale from Maryland districts across the river could be persuaded to abstain when the Senate again sent assumption back to the House as an amendment to the funding bill…By this account, the dinner on June 20, 1790, at Maiden Lane was a historic event and marks the first significant compromise in the history of the federal government. Whether it happened just the way Jefferson recalled or was a less ad hoc series of negotiations does not detract from the obvious fact that some sort of bargain took place that salvaged Hamilton’s plan and placed the permanent capital on the Potomac. It was a first in the American government, but it would be the last for the men who made the arrangement.”

This sense of compromise and working together would unfortunately only last so long: “By early 1792, Washington’s cabinet and informal advisers divided on almost every question that came before them. The pattern of Hamilton and Knox taking one side and Jefferson and Randolph the other was well established by this time.” At this point in American politics, there was no such idea as a “loyal opposition” so those within the government, like Jefferson and increasingly Madison, who began to oppose Hamilton’s proposals consistently and vehemently were presumed to be in a conspiracy to overthrow it – there was no other way to conceive of it at the time. On the other side, Jefferson and Madison were convinced that Hamilton was a monarchist Hamilton’s congressional victories on assumption and later the establishment of the bank would prove too much for Jefferson and Madison. The possibility was there that Hamilton and Jefferson could work together in great complement (as they had largely done before 1792), but eventually their relationship grew too partisan and would produce our first two major American parties as well as put an end to several key relationships: “Thinking the future of the country was at stake made them vicious. By 1792 Madison, Jefferson, and their followers believed their opponents wanted a monarchy or something resembling one…Washington consoled himself that they were men of principle and would not let personal animosity cloud their judgment. He liked to believe that, at least.”